Repackaging shelf-stable products

For products that start out shelf stable but are labeled "refrigerate after opening," I'm wondering if it's possible to safely return them to their shelf-stable status to save refrigerator space. A few specific products come to mind: olives, maple syrup, salad dressing.

For example, could a vacuum sealer and a sterilized jar work? Or does exposure to germs in the air compromise the food requiring refrigeration?

Best Answer

Exposure to germs is the problem, once you open these they are exposed and the clock starts. If you vacuum seal you are vacuum sealing the germs in with the food, and not taking steps to kill the pathogens. Pouring into a sterilized container again just puts contaminated food into an uncontaminated container.

The only way to make them shelf stable again would be to process them. You could vacuum seal and then pasteurize the food inside for example, or re-can and pressure-cook. This takes a lot of time and energy, and each time you do it you lose quality.

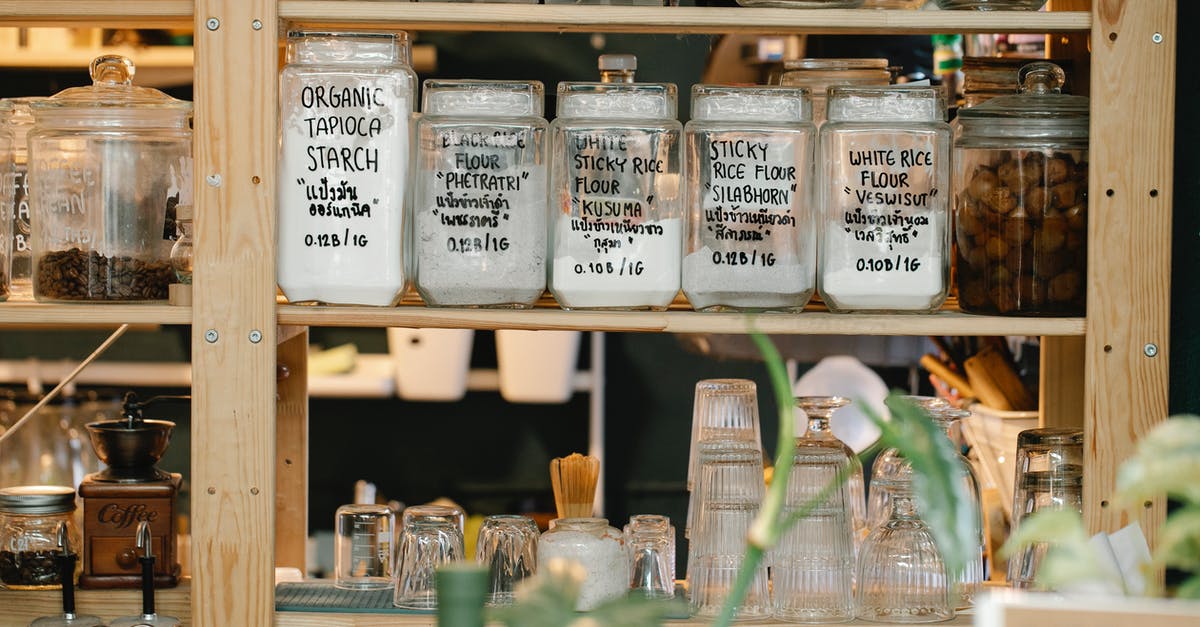

Pictures about "Repackaging shelf-stable products"

What is a shelf stable product?

Foods that can be safely stored at room temperature, or "on the shelf," are called "shelf stable." These non-perishable products include jerky, country hams, canned and bottled foods, rice, pasta, flour, sugar, spices, oils, and foods processed in aseptic or retort packages and other products that do not require ...How do you prolong the shelf life of your products?

How do you find the shelf life of food products?

The shelf life of a product begins from the time the food is prepared or manufactured. Its length is dependent on many factors including the types of ingredients, manufacturing process, type of packaging and how the food is stored. It is indicated by labelling the product with a date mark.What is the shelf life of the product?

A product's \u201cshelf life\u201d generally means the length of time you can expect a product to look and act as expected and to stay safe for use. This length of time varies, depending on the type of product, how it is used, and how it is stored.3 Ways To Increase Shelf Life For Food and Beverage NATURALLY with Packaging

More answers regarding repackaging shelf-stable products

Answer 2

The first question is maybe how long they should last after opening? A week or two? Months? Years?

The second question is IMHO the "mode" of spoiling for that produce and what conservation agents are there already. For some produce this is quite doable:

sugar as conservation agent:

Syrups with sufficiently high sugar content (> 80 % or so, that is like honey) can usually be kept in bottles outside the fridge for months after opening.

In case it's in a can originally, I'd put it into a bottle that can be properly closed to keep dust etc. out and also so that one can see if bad things happen.

The same is true for old-fashioned, very concentrated plum butter and the like.

However, most jams/marmalades/jellies that are sold in sealed jars have lower sugar content and are subject to molding outside the fridge or even in the fridge within a week or so. With them, if you find you get only far larger containers/cans than needed, you can also "re-can" this into smaller jars (though, the smaller the jar, the more difficult it is to achieve the required temperature for content + jar - consider putting either the empty jars or the filled jars into the oven)A special subset of this are some fruit that naturally contain further conservation agents (e.g. lingonberries contain ascorbic, salicylic and benzoic acid)

Acidic brine can also be used to preserve, but again the usual produce sold canned with brine or pickled for immediate consumption do not have sufficiently salty and/or acidic brine to rely purely on the brine for conservation. Or avoid further conservation agents like nitrite.

Expect that the old-fashioned sourkraut in the ceramic jar was far more acidic than what you take out of a can - and moreover the preservation relied pretty much on the opposite of sterilization: it relied on "good" lactobacteria being in such an overwhelming majority that no other microorganisms could thrive [and that is probably again related to these bacteria producing a very acidic microclimate where they are fine, but most other microorganisms are not].A third category would be dried stuff like olives or tomatoes in oil: here the main modes of spoiling are a) sufficient moisture getting in to allow microbial growth and b) the oil going rancid.

Moisture can be avoided by being careful when taking out olives/tomatoes, and by using a proper lid on the container. Rancidity can come from hydrolysis (water, see moisture) and/or from oxidation by oxygen from the air. So: use a gas-tight lid. If the whole glass will be eaten within a few occasions over a few weeks, that's probably sufficient. Otherwise, vacuum sealing would help here.

If the contents in oil are not properly dried, you need to be more careful, but then their shelf life is limited even while still sealed as the moisture together with even low acidity leads to acid-catalysed hydrolysis of the oil, i.e. this stuff will quicky go rancid. (And double-quick at room temperature, so I'd expect such produce to be sold as requiring refrigeration even before opening)

In all cases you also want to be serious about basic food hygiene procedures like taking out a portion of jam for the meal served with a fresh spoon, immediately closing the pot and maybe not even taking that stock to the table.

Last but not least, there is a difference between storage that is merely safe and storage that keeps the full quality. For most products over here (Germany), the instructions on the label are to conditions under which the producer guarantees full quality including taste, smell and color*.

E.g. many syrups loose flavor over time while they are still perfectly edible. Many of the processes involved in that are slower at lower temperature - so the producer chooses to label "use within 3 weeks after opening, keep refrigerated" rather than "use within 1 week after opening [no refridgeration]"

Another example are fruit preserves that are perfectly safe to eat after decades if the canning was done correctly (and if it was not done correctly, that's obvious comparably soon). But the sugar will be inverted due to the acid, and they'll have lost most of their taste and color with be a universal grayish-brown. So safe to eat, but not so enjoyable (one taste that stays, though, is the unripe taste of gooseberries - I can attest to preserves that even after 2+ decades in the jar still tasted horribly unripe...).

* They are labeled as "best before" if the label says "consume before" then after that date there is a substantial risk of the food being unsafe to consume.

The salad dressing in your list, OTOH is not a candidate for extended shelf life after opening. It will likely contain a nice mixture of water, carbohydrates, lipids and protein and is thus a very good growth medium for all kinds of microorganisms (and in addition, "funny" things may happen if you cook it).

Unless you are talking of a vinaigrette - but then that in itself does not last long since we're back to acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of the oil.

Sources: Stack Exchange - This article follows the attribution requirements of Stack Exchange and is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Images: Pixabay, Artem Beliaikin, Tima Miroshnichenko, Sarah Chai