Ingredients vs. Temperature Control in Chocolate Fudge

In reading through a LOT of different approaches to making fudge, I am wondering about how the non-sugar ingredients affect the issue of temperature control (both heating AND cooling) and, therefore, the results in the recipes.

First of all, a question about heating the sugar solution - am I correct that in bringing a sugar solution to the soft-ball stage temperature, what you are doing technically is boiling-off water to the point where the sugar concentration is appropriate for the re-crystallization properties desirable in fudge? So, the temperature gives you an indication of the concentration of sugar in solution and different concentrations behave differently when cooled, is that right? Basically, the temperature is documenting sugar concentration achieved by way of evaporation.

If that is true, then I can buy that in heating the sugar and milk or cream or condensed milk to make fudge, the temperature would still be dictated by sugar concentration in the water part of the milk-product. So if we think of a a milk-product as water + solids + fats, the sugar concentration is still reliably documented by the temperature since the sugar will dissolve in the water of the milk and is (basically) unaffected by the solids and fat content. Is that, more-or-less correct?

Continuing along this same line of reasoning, would it also be correct to assume that as long as you add to the pot only ingredients that contain NO water, that you would preserve the integrity of the relationship between the temperature of the ingredients and the concentration of sugar in solution? So heating the chocolate or marshmallow (or whatever) with the milk/sugar solution won't fundamentally alter the relationship between sugar concentration and temperature?

Then what about adding ingredients during cooling? Most recipes where you heat all of the ingredients together (except butter and vanilla) instruct you to let the mixture sit undisturbed until it cools to (like) 110° F - I thought that the goal there is to have the sugar in a supersaturated state so that crystallization will occur rapidly when you stir.

But some recipes instruct you to add other ingredients after bringing the sugar/milk to the soft-ball stage - I would think that adding ingredients during cooling could induce a temperature change that could screw-up the supersaturated state and give you grainy fudge. Most of these types of recipes contain marshmallow. So, since marshmallow is mostly corn syrup, is the corn syrup controlling the re-crystallization properties of the sugar? If that's true, do you need to be careful with a marshmallow fudge during cooling at all?

Best Answer

I think you may well be over thinking this just a little.

Water boils at 100c at sea level, sugar raises this temperature to around 110c depending on sugar content.

Specifically, adding 1 gram molecular weight of nonionizing solute (like sugar) to 1 liter of water increases the boiling point by 0.52 degree Celsius (C). 1 gram molecular weight nonionizing solute per liter =0.52 degree C increase in boiling point.

So when you boil your sugar syrup to soft ball 116c you've essentially, boiled all the water away and your left with sugar. Heating it to this temperature changes the shape and direction of the crystals. Adding fat to this generally allows it to set (plus flavour). Just as butter would.

The reason you don't add chocolate as it's warming is water plus chocolate ends badly. You also don't add it at 116c as you will burn your chocolate. Again not a good thing.

Make sure the temperature of the chocolate rises to between 104° F. and 113° F. when melting. Do not heat above 115° F. (milk and white chocolate) and 120° F. for dark chocolate, otherwise it will burn.

The reason you add water to sugar is to allow more control over the heating. If you have no water you'll find the bottom part will burn while the top part is still solid crystals. Which considering you only need 116c, is again... Bad.

Try boiling 1000ml water with 100g sugar and see how quickly it takes for the mixture to reach 110c (5min?) and then see how long it'll stay at that temperature before hitting 116 (30-40mins I guess). Then leave it and watch how within moments of hitting 116c it's suddenly hit 176c and then your pan turn black and your kitchen full of thick yellow smoke :-).

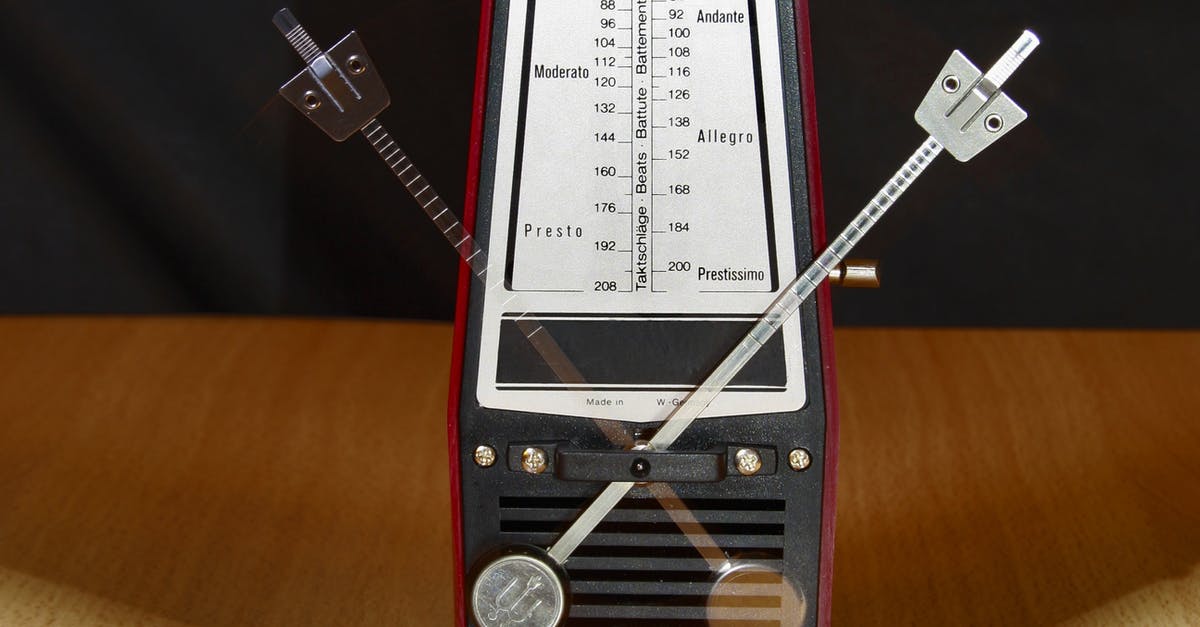

Pictures about "Ingredients vs. Temperature Control in Chocolate Fudge"

What temp should you cook fudge to?

You have to control two temperatures to make successful fudge: the cooking temperature AND the temperature at which the mixture cools before stirring to make it crystallize. Confectionery experiments have shown that the ideal cooking temperature for fudge is around 114 to 115 \xb0C (237 to 239 \xb0F).How do you make perfect fudge?

Here are some tips to help you make your best fudge:What is the purpose of corn syrup in fudge?

Why do I add corn syrup? Corn syrup acts as an "interfering agent" in this and many other candy recipes. It contains long chains of glucose molecules that tend to keep the sucrose molecules in the candy syrup from crystallizing.How do you make fudge harder?

Use powdered sugar. Instead of adding evaporated milk, add some powdered sugar and remix your fudge batter. The powdered sugar can help the fudge set and harden if it is resistant to doing so.Only 2 Ingredient Chocolate Fudge Recipe (Perfect for gift giving)

More answers regarding ingredients vs. Temperature Control in Chocolate Fudge

Answer 2

Heating and cooling is one of the trickiest subjects to baking right after tempering eggs and plain old understanding the product you are working with. One thing to remember with chocolate is that it will literally melt in the palm of your hand so high heat and chocolate don't mix. You can temper chocolate although by bringing to 110 degrees Fahrenheit and then cooling it back to room temperature. Any way more information than I was originally going to share. My advice tour a bakers kitchen of a experienced chef w/ 25+ years. Books are great but first hand mistakes and accomplishments are the only true way to really know.

A rainy day can change the outcome of your recipe!

Sources: Stack Exchange - This article follows the attribution requirements of Stack Exchange and is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Images: Annelies Brouw, Mike B, Pixabay, Malte Luk